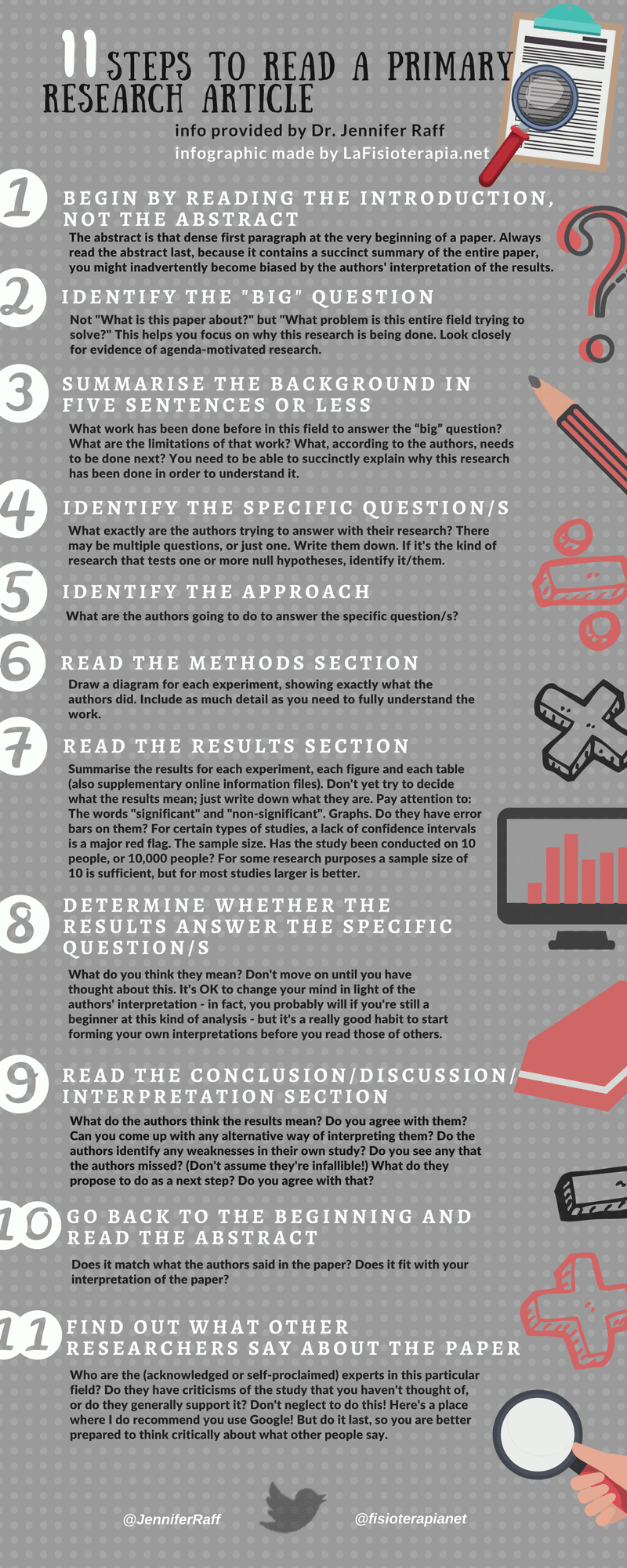

This information has been kindly provided by Dr Jennifer Raff. I hardly recommend you to read the original full text How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists to get a better understanding of the information provided here.

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. Always read the abstract last, because it contains a succinct summary of the entire paper, you might inadvertently become biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the “big” question

Not «What is this paper about?» but «What problem is this entire field trying to solve?» This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less

What work has been done before in this field to answer the “big” question? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next? You need to be able to succinctly explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the specific question/s

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the specific question/s?

6. Read the methods section

Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work.

7. Read the results section

Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean; just write down what they are. Pay careful attention to the figures and tables! You may also need to go to supplementary online information files to find some of the results. Also pay attention to: The words «significant» and «non-significant.» Graphs. Do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag. The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10 people, or 10,000 people? For some research purposes a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better.

8. Determine whether the results answer the specific question/s.

What do you think they mean? Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s OK to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation — in fact, you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis — but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/interpretation section

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Go back to the beginning and read the abstract

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. Find out what other researchers say about the paper

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it? Don’t neglect to do this! Here’s a place where I do recommend you use Google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

Spanish version